So-called reverse acquihires have left once-promising startups stranded, with remaining employees left to figure out what to do next.

Dominic Perella was prepared to be yelled at when he addressed about 100 employees gathered at the posh Silverado Resort in Napa, California, for a staff retreat last August. Days earlier, Perella had become Character.AI’s interim chief executive officer when the company announced that Noam Shazeer and Daniel De Freitas, the renowned artificial intelligence researchers who founded the startup three years earlier, had exited for Google as part of a $2.7 billion licensing deal with the search giant.

During a no-holds-barred Q&A, Perella’s employees—who’d previously known him only as general counsel—grilled the new boss about Character’s future. “What are we going to keep doing? What are we going to stop doing? How are we going to shift our resources?” Perella recalls them asking. “Having your founder leave is a big change,” he says. Still, he insists the company is doing well by the standards of startups that have gone through a novel form of transaction known as a reverse acquihire. “We were left much better positioned than some of the other folks.”

Character is one of at least six startups that have gone through a reverse acquihire during the current AI boom. The name is a variation on what’s known as an acquihire, where a company buys a startup as a way to get its employees on its staff; the new twist is that a Big Tech company pays to hire a startup’s top talent and license its technology but not acquire the company itself. The remaining crew is left to pick up the pieces.

For the tech giants, the deals are a way to gain advantage in the brutal AI talent wars. They also offer many of the benefits of traditional acquisitions without the need for government approval, a process that has become more fraught as officials express concern that big companies may choke off competition by buying potential rivals still in their infancy. “Under the current regulatory regime, I expect more of these to happen,” says Mike Volpi, a venture capitalist and board member at Scale AI, which was reverse-acquihired by Meta Platforms Inc. in June.

The deals also strip startups of key leadership and limit their opportunities in other ways. They often don’t provide employees or investors with the kind of windfall that comes from a traditional acquisition or public listing. Volpi admits they “can create misaligned incentives.” Still, he says, “it’s better than no deals at all.”

The rise of such deals could even make it harder for startups to hire in the first place, says Saanya Ojha, a partner at Bain Capital Ventures. “You don’t want the default assumption to become ‘Hey, we never know when you’re just going to get gutted out by Big Tech, and might as well go straight to OpenAI, Anthropic or even Big Tech,’” she says. Critics also worry the tactic undermines Silicon Valley’s social contract—the idea that founders and employees work toward a shared goal and split the upside. “At some point the acquirer and the founder decide who comes along and who is essential for the journey ahead, and everyone else is left back on the ghost ship,” says longtime venture capitalist Jon Sakoda, who’s critical of reverse acquihires. “You have to figure out if I am on Noah’s Ark or am I on the Titanic.”

Financial returns on the reverse acquihires have varied widely. When Scale CEO Alexandr Wang joined Meta as part of a $14.3 billion investment in the company, Accel, an early investor, expected a $2.5 billion windfall. Backers of Adept AI Labs and Covariant, a pair of AI startups that both lost their founders to Amazon.com Inc. last year, reaped far more modest returns. There’s also the question of whether they’ll retain their utility as a way to avoid antitrust scrutiny—the Federal Trade Commission has opened investigations into several of them.

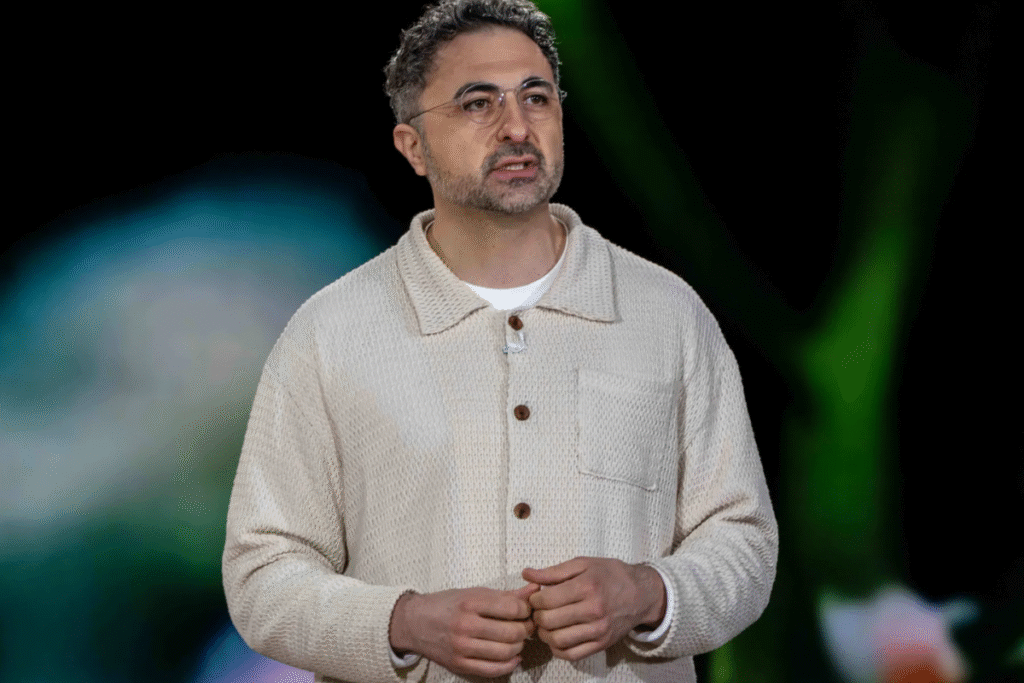

The reverse-acquihire trend started in earnest in March 2024, when Microsoft Corp. hired away the founders of the chatbot startup Inflection AI, along with most of its staff, as part of a $620 million licensing deal. It was a shock to Silicon Valley. While acquihires have generally provided face-saving off-ramps for startups that no longer seem destined to hit it big, Inflection was seen as a promising early AI entrant. Less than a year earlier it had raised $1.3 billion at a $4 billion valuation. But behind the scenes, Inflection co-founder and CEO Mustafa Suleyman had realized that staying independent would mean spending a majority of his time fundraising, and even that might not keep Inflection viable, given it was going up against tech’s biggest companies, according to an account in Gary Rivlin’s book AI Valley. So last spring, Suleyman accepted Microsoft’s offer to join the company.

Microsoft AI CEO Suleyman speaking at a Copilot event in April.Photographer: Winni Wintermeyer/Washington Post/Getty Images

Inflection hired former Mozilla executive Sean White as Suleyman’s replacement. White called the remote staff back to the Palo Alto office, which was so sparsely populated that it barely had any furniture. He bought new desks and chairs just so he wouldn’t have to keep sitting cross-legged on the carpet, along with some plants. He allowed employees’ dogs to roam freely. The company has made several small acquihires of its own to bolster its 55-person staff and has targeted people drawn to the culture of a startup in its general hiring efforts.

Under White’s upbeat leadership, Inflection shut down its consumer-focused “Pi” chatbot and pivoted to serving enterprise clients such as Intel Corp. It retains a trove of consumer data from Pi’s previous users, which White says should help it fine-tune a more socially competent chatbot for businesses. More than a year later the startup is still in rebuilding mode, he says, invoking the Greek myth of the Ship of Theseus. “The ship, over time, was slowly replaced, board by board, piece by piece, right? But it was still always the same ship.” He says the company plans to raise more money again soon.

Scale AI, which was left with most of its 1,400 employees after the Meta deal, is also shifting its focus. Its main business was labeling data for large language model developers, and major customers including Google and OpenAI have paused their spending with the company because of their rivalry with Meta. Scale cut 14% of its staff, all from the data-labeling division. The startup says it now plans to focus on expanding its business in custom enterprise and government AI applications under interim CEO Jason Droege, its former chief strategy officer. Droege also has the difficult task of maintaining employee morale after Wang’s departure. “We have to be honest with people—Alex is the founder, he’s an iconic entrepreneur, and he moved heaven and Earth to build this business from scratch nine years ago,” he says. “But there’s still an enormous opportunity ahead for us.”

Like Inflection and Scale, Character has had to change its business model, moving away from a costly effort to train its own LLMs and focusing exclusively on developing its AI characters. Since that 2024 off-site, the startup has attempted to soothe employees’ frustration by providing monthly cash payouts equivalent to their unvested equity, according to people familiar with the matter who asked not to be named discussing private information. Character will continue to do so for two years after the reverse acquihire—using funds from the Google licensing deal, says one of the people. The company plans to raise money again, according to Karandeep Anand, a former vice president at Meta who was named permanent CEO in June. (Perella remains with the company as its chief legal officer.)

For the leadership team at AI coding developer Windsurf, a $2.4 billion licensing deal with Google seemed like a soft landing after a planned $3 billion sale to OpenAI fell apart. Jeff Wang, the startup’s head of business, remembers how the departing executives broke the news to him. “They just said, ‘Hey, Jeff, it’s kind of a Character AI situation, and you’re going to have to be the CEO,’” he says. “It felt like the weight of the world just fell on my shoulders.” The deal was rough on other remaining employees, some of whom spent most of that Friday in tears. But by Monday they’d been rescued: Cognition, another AI coding company, agreed to purchase Windsurf’s remaining assets in a nine-figure deal, Bloomberg has previously reported.

No one swooped in to save Covariant, a robotics lab, which lost three of its founders and 25% of its staff as part of a $380 million Amazon licensing deal last year. Covariant CEO Ted Stinson complained that the deal undermined the startup by restricting the kinds of licenses Covariant could sell, according to a whistleblower’s

filing cited in the Washington Post. Stinson declined to comment through a spokesperson. In an emailed statement, Amazon spokesperson Alexandra Miller said it had an agreement that included a “non-exclusive license to Covariant’s robotics foundation models,” meaning the startup is “free to license its technology to other companies.”

For Adept, an enterprise AI startup, the deal with Amazon came before it even launched a product. Adept’s backers recouped their investment but didn’t turn a profit. Its head of engineering, Zach Brock, stepped in as CEO but left for OpenAI less than a year later. Only four people still list Adept as their employer on LinkedIn. (None responded to requests for comment.)

As of now it’s unclear who, if anyone, is running the company. —With Yazhou Sun